Blackout as a Possible Cause of Death

A FAMILY STORY

A British/Dutch family recently contacted me to make sense of an important chapter of their family history. It raises an interesting question: was the motorcycle accident which led to TE’s death the consequence of a blackout?

Imagine yourself in Lincolnshire (England) in 1929. Fifteen-year-old Joyce is walking home from work. While coming down Cross O’ Cliff Hill, she sees a large motorcycle on its kickstand at the side of the road with the engine still running. After looking around, she spots a man lying in a ditch. He is in quite a bad way, shaking, sweating and delirious, speaking a load of nonsense. She turns the motorcycle off and struggles to take the man to her home, which is a few miles away in the city of Lincoln. Her mother immediately tends to him, while her older brother goes off to fetch his bike. The man, who is well looked after for a few days, bears the name Shaw and serves in the RAF. (*1)

Imagine yourself in Lincolnshire (England) in 1929. Fifteen-year-old Joyce is walking home from work. While coming down Cross O’ Cliff Hill, she sees a large motorcycle on its kickstand at the side of the road with the engine still running. After looking around, she spots a man lying in a ditch. He is in quite a bad way, shaking, sweating and delirious, speaking a load of nonsense. She turns the motorcycle off and struggles to take the man to her home, which is a few miles away in the city of Lincoln. Her mother immediately tends to him, while her older brother goes off to fetch his bike. The man, who is well looked after for a few days, bears the name Shaw and serves in the RAF. (*1)

You can follow this story on the map.

Point A: Place where Shaw was lying at the side of the road.

Point B: Joyce’s home, where Shaw was looked after.

Point 2: RAF Cranwell, where Shaw was based in 1925 and 1926.

For me the most interesting part of this story is the fact that TE (who called himself Shaw at that time) became unwell, and had to park his motorcycle at the side of the road to come to his senses. This is especially interesting because the combination of riding a motorcycle and having fits might have played an instrumental role in the accident which caused his death.

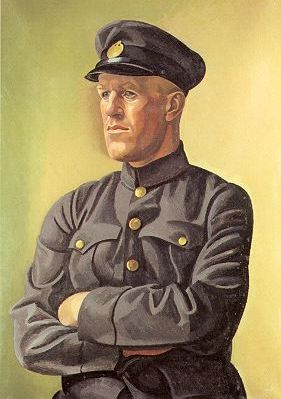

MOTORCYCLING

TE had a serious passion for motorcycling, and rode the best model going: the famous Brough Superior. Riding it helped him through difficult times. Because of his war and rape trauma, he suffered from depression, and sometimes he was on the verge of madness. To chase off “the broody feeling” (*2) and the restlessness, “movement fast in the night” helped him to temporarily cure his mind. (*3) “When my mood gets too hot and I find myself wandering beyond control I pull out my motor-bike and hurl it top-speed through these unfit roads for hour after hour. My nerves are jaded and gone near dead, so that nothing less than hours of voluntary danger will prick them into life; and the ‘life’ they reach then is a melancholy joy at risking something worth exactly 2/9 a day.” (*4)

Sometimes he drove like a madman, with speeds up to 108 miles an hour (173,5 km). (*5) Consequently he also had accidents. For example in May 1926 he got caught with his wheel in a tramline, which left him bleeding from the head and unconscious for a short while. (*6) Later that year he cracked his knee in another accident, ruining his bike. (*7)

Sometimes he drove like a madman, with speeds up to 108 miles an hour (173,5 km). (*5) Consequently he also had accidents. For example in May 1926 he got caught with his wheel in a tramline, which left him bleeding from the head and unconscious for a short while. (*6) Later that year he cracked his knee in another accident, ruining his bike. (*7)

BLACKOUTS

In this story, we find TE lying in a ditch, suffering from what appears to be a traumatic black-out. The first time I heard of TE’s blackouts was in an exchange of letters between his two friends, Celandine Kennington (*8) and Jim Ede (*9), where they speak about witnessing TE having “epileptic fits”. (*10) It did not make sense to me at that time, because I had never heard any mention of it before. But during my research on trauma, I found that there were more soldiers and officers from the First World War who suffered from fits.

These fits were anxiety reactions, caused by dissociated traumatic memories, which would suddenly and unexpectedly take over. They made the victim act as if he were again experiencing the traumatic situation, leading to violent fright and panic, just as in the original events or even worse. Psychosomatic symptoms, like shaking and shivering all over and losing consciousness, are the nervous system’s attempt to contain the intense survival energies that remain in body and mind as the result of unresolved trauma. Reliving these traumatic memories would occur in nightmares or even night terrors during sleep, and in flashbacks and dissociative episodes during the day.

TE had them all. Horrible dreams made him afraid of going to sleep, leading to insomnia and to an intensification of his symptoms because of exhaustion. The flashbacks and episodes during the day led people to wonder if TE was practising meditation or yoga, because he could suddenly “go dead”, sitting in the same position for hours, without moving and with the same expression on his face. Others considered him to be moody and introspective, because he could suddenly shut himself off in the middle of a conversation and seem to be miles away.

TE had them all. Horrible dreams made him afraid of going to sleep, leading to insomnia and to an intensification of his symptoms because of exhaustion. The flashbacks and episodes during the day led people to wonder if TE was practising meditation or yoga, because he could suddenly “go dead”, sitting in the same position for hours, without moving and with the same expression on his face. Others considered him to be moody and introspective, because he could suddenly shut himself off in the middle of a conversation and seem to be miles away.

Blackouts are usually triggered by cues that remind the victim in some way of the traumatic situation, or by new situations which cause feelings of powerlessness and fear. TE’s writing about his experiences, though helpful for integration in the long run, possibly made his situation worse. Particularly because of his ambitions surrounding it, to fulfil his wish to become a creative artist, and write one of the great books of his time, like Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Melville’s Moby Dick. His consciousness became dominated by remembering, and by again being awash with the emotions and sensations involved, which may have been traumatizing in itself.

After a blackout, the victim does not remember a thing: he has blacked out. If anything, he only knows that time has been inexplicably lost. Losing control over his own body and mind must have horrified TE, since self-control was essential to him. Therefore it must have come as a great shock to learn that it was not his reason, but the “traitors from within” (*11), which ruled him. His will proved to be unable to neutralize the traumatic images which caused emotional outbursts. If his will was not able to control his inner self, who or what would? To make it even worse, reliving traumatic experiences and emotions sometimes bring about an extreme consciousness of repressed and negated feelings. Thus old fears and possibly old traumas, which had been successfully suppressed, also came to the surface again. As TE says, “there is the school-fear over me”. (*12)

It should be clear by this point, that it is very easy to underestimate the importance and influence of these blackouts on TE’s life after the war. Having sudden and continuous re-experiences of his rape and war trauma, in the form of blackouts and nightmares, and bringing with it a return of old fears from his childhood, meant an enormous attack on his mental and physical stamina, and brought TE to the verge of madness. Fear and anxiety dominated his life: “Fear again; fear everywhere.” (*13) Fear of people, fear of a repeat of the events, fear of a loss of control. He felt himself to be excessively vulnerable, powerless and helpless. To deal with his fears and to protect himself from his own frightening reactions, he chose an ordered life for himself in the armed forces, as an ordinary private, while he also started to study the psychology of fear. (*14)

It should be clear by this point, that it is very easy to underestimate the importance and influence of these blackouts on TE’s life after the war. Having sudden and continuous re-experiences of his rape and war trauma, in the form of blackouts and nightmares, and bringing with it a return of old fears from his childhood, meant an enormous attack on his mental and physical stamina, and brought TE to the verge of madness. Fear and anxiety dominated his life: “Fear again; fear everywhere.” (*13) Fear of people, fear of a repeat of the events, fear of a loss of control. He felt himself to be excessively vulnerable, powerless and helpless. To deal with his fears and to protect himself from his own frightening reactions, he chose an ordered life for himself in the armed forces, as an ordinary private, while he also started to study the psychology of fear. (*14)

DEATH

The family story told here indicates that it is very likely that TE had more incidents caused by black-outs, both with and without his motorcycle. Therefore I would like to suggest a connection with his fatal accident on May 13, 1935. While riding his motorcycle that day, he suddenly came upon two boys on bicycles in a dip of the road. He swerved to avoid them, which caused him to be thrown from his machine. It was a strange accident, because TE knew the road extremely well, having lived nearby since 1923. Therefore he would have experienced traffic regularly on that particular stretch of road. Besides, he was only doing 40 miles an hour, which for an experienced rider like TE was nothing special, and would have given him enough time to react in the event of an unusual occurence. A sudden blackout would explain this otherwise inexplicable accident, which left TE unconscious. After six days in a coma, he died in hospital on May 19, 1935 from severe brain damage. (*15)

NOTES

*1 Shaw, as TE called himself officially in those days, was at that time based at RAF Cattewater, in Plymouth (Devon), after his sudden return from India in February 1929. From August 1925 until November 1926, he had served near Lincoln, at RAF Cranwell, which is merely 13½ miles from the place where this story starts. Therefore he might have been visiting old friends at Cranwell. Another reason for being in Lincoln at that time could have been a visit to the motorcycle factory of George Brough in Nottingham (32 miles from Lincoln), for a check-up to his brand new motorcycle.

*2 Letter from TE to Charlotte Shaw 26-12-1925, in: Jeremy & Nicole Wilson (eds.) – T.E. Lawrence Correspondence With Bernard And Charlotte Shaw 1922-1926 (Castle Hill Press 2000),p.158

*3 T.E. Lawrence – Seven Pillars Of Wisdom (Jonathan Cape, London 1935),p.518

*4 Letter from TE to Lionel Curtis 14-5-1923, in: Malcolm Brown (ed.) – The Letters Of T.E. Lawrence (J.M. Dent & Sons, London 1988),p.237

*5 Letter from TE to John Buchan 5-7-1925, in: David Garnett (ed.) – The Letters Of T.E. Lawrence (Jonathan Cape, London 1938),p.478

*6 Heanor & District Local History Society Newsletter 234 (1999), quoted on T.E. Lawrence Studies List 23-11-1999.

*7 Letter to Pat Knowles 30-11-1926, T.E. Lawrence Studies List 19-6-1998.

*8 Celandine Kennington (1886-1975), usually known as Mrs Kennington, was the wife of Eric Kennington (1880-1960) the artist who worked with TE on Seven Pillars of Wisdom. TE became friends with both Eric and his wife. She was suffering from manic depression, and felt a special connection with both TE, who comforted her on a few occasions, and his mother.

*8 Celandine Kennington (1886-1975), usually known as Mrs Kennington, was the wife of Eric Kennington (1880-1960) the artist who worked with TE on Seven Pillars of Wisdom. TE became friends with both Eric and his wife. She was suffering from manic depression, and felt a special connection with both TE, who comforted her on a few occasions, and his mother.

*9 Harold Stanley Ede (1895-1990), better known as Jim Ede, was assistant curator at the Tate Gallery from 1921 to 1936. It became his vision that art should be shared in a relaxed environment and not in a museum, and he put this open house principle into practice by opening up the wonderful art collection in his house Kettle’s Yard (in Cambridge) to the public. He left it to the  University, and I would definitely advise you to visit it, if you have the chance. Ede was a very sensitive man, and suffered an emotional disturbance in the latter part of 1929. While he tended to blame the war for his difficulties, TE tried to help him obtain a more balanced perspective. He wrote that TE “by his kindly sanity on his various visits helped me considerably at this period.” After his death in 1935, Ede started working on a biography about TE, but became depressed studying his life, and never finished it.

University, and I would definitely advise you to visit it, if you have the chance. Ede was a very sensitive man, and suffered an emotional disturbance in the latter part of 1929. While he tended to blame the war for his difficulties, TE tried to help him obtain a more balanced perspective. He wrote that TE “by his kindly sanity on his various visits helped me considerably at this period.” After his death in 1935, Ede started working on a biography about TE, but became depressed studying his life, and never finished it.

*10 Correspondence in Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.

*11 T.E. Lawrence – Seven Pillars Of Wisdom (1935),p.468

*12 T.E. Lawrence – The Mint (Jonathan Cape, London 1973),p.154

*13 Letter to Charlotte Shaw 28-9-1925, in: Malcolm Brown – The Letters of T.E. Lawrence,p.290. Chapter 4 of his memories of his life in the Tank Corps and the RAF, The Mint, is titled “The Fear”. “The root-trouble is fear: fear of failing, fear of breaking down.” (The Mint,p.154). “For a moment my bedfellow was perfect fear.” (The Mint, p.24)

*14 Arnold Lawrence in: A.W. Lawrence – T.E. Lawrence By His Friends (Jonathan Cape, London 1937),p.590

*15 The film fragment of David Lean’s Lawrence Of Arabia (1962) showing TE’s accident, was not filmed at the original location in Dorset, but on a minor road outside Chobham in Surrey. It must be noted too, that in reality the boys on the bicycles were not cycling towards TE, but were riding in the same direction, probably on the wrong side of the road.